While scrolling through my Facebook feed the other day, I saw this video a divorcee coworker had shared about a woman named Andrea’s journey through divorce.

Andrea begins with her story of how her first husband one day suddenly admitted his infidelity and lack of commitment to their marriage and left her, broken and pregnant. “There were so many stories that I had heard from other about marriages coming out even stronger, and I wanted to be one of those stories,” she says. “But it was pretty apparent than mine wasn’t going to be one of those stories.” The video continues and introduces Brian, the second husband, stepfather to Andrea’s two sons, and biological father to three more of her children. The video takes a dark turn, however, when around 4:11 into the video Brian says, “I tell my friends [that they should] marry divorced girls.” This is not a sentiment that a healthy society professes.

I do not know whether Andrea’s account of the demise of her marriage is accurate, as husband #1 is not there to give his side of story. However, this essay was not written pass judgment on Brian and Andrea’s family, but as a counter to the video’s rose-colored glasses view of divorce, to Andrea’s portrayal of the post-divorce family as normal, and to Brian’s assertion that divorcees are desirable as romantic partners. This depiction is pure deception. Divorce is a scourge to properly-functioning society and victimizes children caught in the storm. I have written this essay to set the record straight.

There is nothing more beneficial to the family than marriage.

Marriage (that is, a first and only marriage) is one of the greatest societal goods—arguably the greatest—and benefits both the couples and the children within the marriage. Some of the many advantages to the married couple include:

- Married individuals are less likely to be the perpetrators or victims of violent crime. Women are four to five times more likely to be the victim of a crime if they are divorced or unmarried.

- Individuals who come from impoverished conditions, get married, and stay married are less likely to continue to experience poverty than unmarried individuals of a similar background.

- Married men make 10%-40% more money than single men of proportionate educational background and work experience. Married men who leave a job are more likely to already have a new job lined up when they leave and are less likely to be fired.

Being raised in a two-parent household by their biological parents is the number one indicator for future success in all areas of life for children—more than all other factors, including socio-economic status and geographical region. Some of the many advantages for children of married parents include:

- Academic achievement, including good grades and high graduation rates from high school and college.

- Strong relationships with parents. Children from married households are half as likely to report unhappy relationships with either parent.

- Good physical health. Children from divorced households are significantly more likely to develop speech impediments, asthma, substance abuse disorders, borderline personality disorder, or suicidal ideations.

Divorce causes harmful separation from one or both parents.

Parents in 23% of divorced households in the United States do not live in the same state as their children’s other biological parent. Forty percent of children from a divorced family have not seen their biological fathers in over 12 months. The little time children from divorced households do spend with their biological fathers is almost always without the biological mother present. Time away from parents of either sex has dramatic effects on childhood physical, educational, and psycho-social development.

One study found that separation of a child from the mother for as little as one week in early childhood causes issues ranging from increased aggression to lower reading achievement. The effects are worse the longer and earlier in life the separation occurs. This is true even when motherly warmth and affection is no different from a child who did not experience a lapse in maternal presence. Absence of or separation of a child from his or her father results in negative outcomes in academic achievement, mental health development, employment, and gender-specific consequences including delinquency in boys and early sexual activity in girls.

Divorce is a social disease.

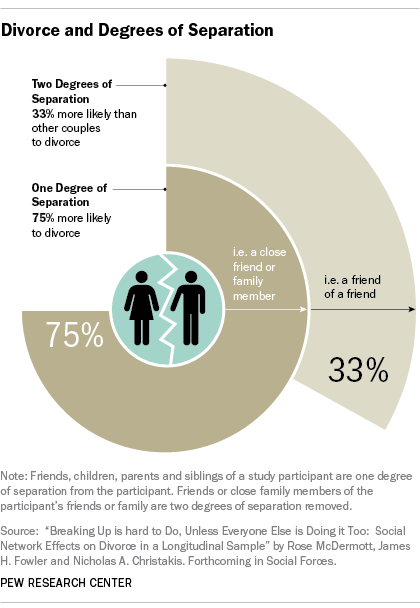

Unsurprisingly, children who experience divorce of their parents are themselves more likely to divorce. Also unsurprisingly, individuals who have divorced and remarried are almost twice as likely to see their second marriage end in divorce than those on their first marriage. But one fascinating study shows that the impact of divorce may go deeper—it may truly be a social disease. In this study, participants were 75% more likely to become divorced if they had a friend who was divorced and 33% more likely to divorce if a friend of a friend were divorced.

For divorce to be contagious outside the family dynamic and even through several degrees of separation has dramatic implications for the role of culture and stigma in containing the spread of divorce and, consequently, mitigating its deleterious effects.

No, cohabitation is not the same

Cohabitation is not a substitute for marriage. Studies of biological, but unmarried, parents living in a cohabitation scenario show more similarities to families in which the primary parent is single or remarried than to married, biological parents. If merely the presence of both biological parents were the benefit of marriage upon children, then we might expect to see greater similarities between cohabitating and married parents, but this is not the case. Conversely, we might also expect to see similarities between children of widowed parents and single or divorced parents, but this is not the case either. Children of widowed parents are half as likely to drop out of school or experience teen pregnancy as children from a divorced family. It appears that there are benefits to marriage beyond simply the presence of both parents. On this, I will not speculate here, but rather leave it as a point for the reader to muse.

Ending the cycle of divorce

Shortly after I was married, I was chatting with a family friend who teaches a marriage course at his church and whose opinion I hold in high esteem. We were casually discussing the excitement and challenges of the early years of marriage, when, suddenly changing his tone and facial expression, he looked at me sternly and said,

The gravity with which he said it struck me. He didn’t seem to be speaking to me directly, or even to me in the context of my marriage, but as part of a more collective “you.” It is incumbent on us, generationally, to break this trend our Baby Boomer predecessors so selfishly normalized. We must make talk of step-families, half siblings, and weekends at Dad’s outmoded. We must expose the delusion of normal post-divorce families for the lie that it is. We can and must stop the normalization of divorce.

There is some good news. Younger generations are divorcing less (or “ruining divorce” as several media outlets have cheekily put it). The majority of marriages do not end in divorce, despite common myths. The divorce rate has fallen 18% from 2008 to 2016, and the 50+ age group is the only age range seeing increases in divorce. The other good news is that 62% of children in the US do live with both birth parents. We in the younger crowd have experienced or witnessed the terrible effects of divorce and have turned our backs on it. This is a solid foundation upon which we can build. We must take our vows seriously, marry without possibility of divorce on the table, and ensure for the wellbeing of our children that we do not inflict the damage upon them that the previous generations have upon us.

References

http://americanvalues.org/catalog/pdfs/why_marriage_matters2.pdf

https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/public/resources-and-publications/states/0086.pdf

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3904543/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3115616/

https://brandongaille.com/52-fascinating-divorce-and-remarriage-statistics/

http://fortune.com/2018/09/25/millennials-ruin-divorce/

http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/10/21/is-divorce-contagious/

https://ifstudies.org/blog/more-than-60-of-u-s-kids-live-with-two-biological-parents/